The internet has been a solution to a whole host of problems introduced by the COVID-19 pandemic, from keeping kids in school to connecting co-workers in their homes. But what does this mean for the billions of people worldwide who still lack internet access?

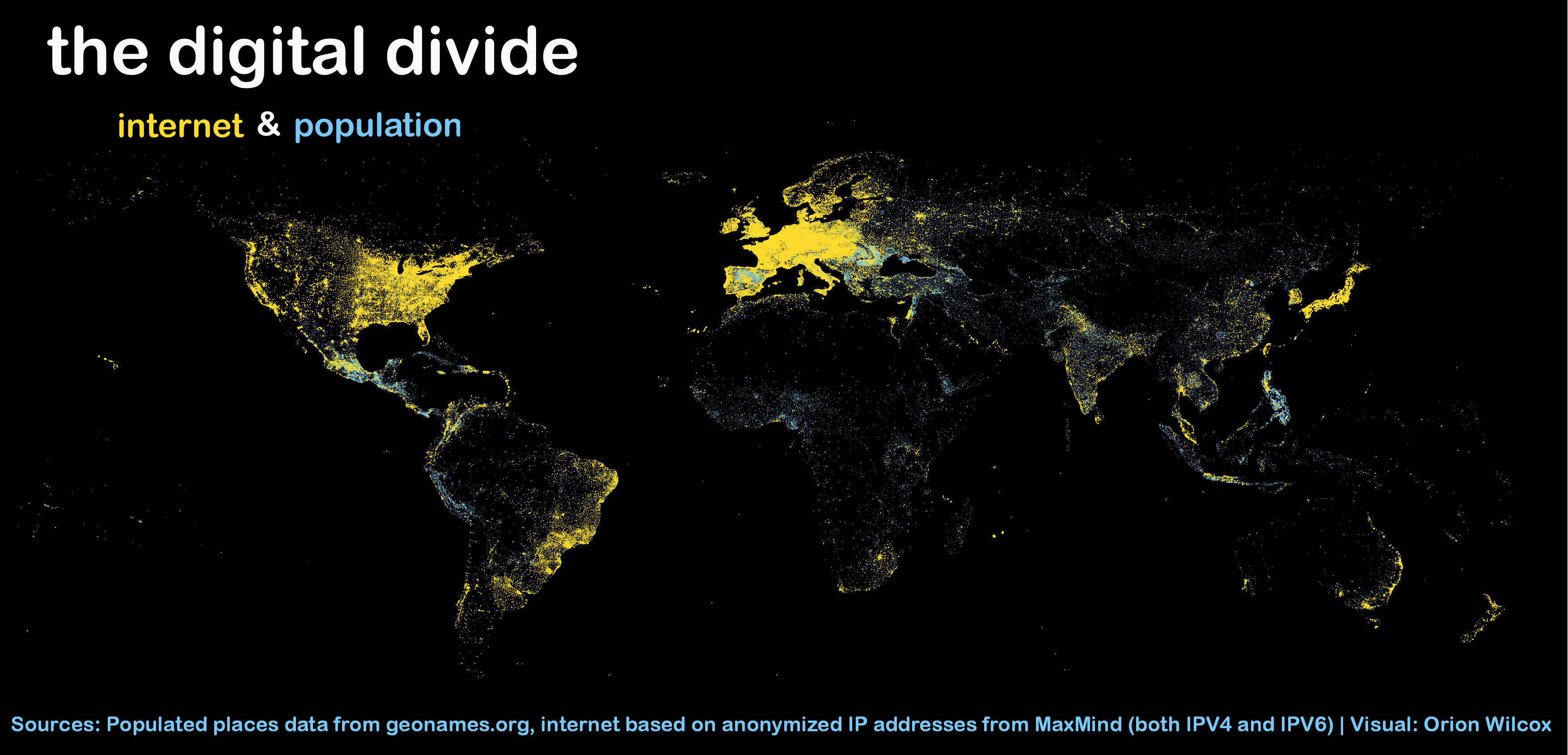

According to UNESCO, only 55 percent of households globally have an internet connection. In the poorest countries, this percentage drops to below 20 percent. The map above highlights this inequality—what researchers refer to as the “digital divide”—by overlaying internet connections (i.e., IP addresses) with population. The blue spots on the map represent people without internet.

While mapping the digital divide in this way helps illustrate the inequities between countries, it obscures barriers to access within countries. For example, globally women are 23 percent less likely to have internet access than men. This divide exists even in countries with high internet penetration. In Iraq, 98 percent of men can connect to the internet, but only 53 percent of women are able to.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is both highlighting these inequalities and exacerbating them. As entire countries go into lockdown and travel is restricted, more and more of our daily lives occur online. Those caught on the wrong side of this divide are disconnected from opportunities for education, services, and employment.

As an international development firm operating in low-income countries around the world, DT Global witnesses these challenges firsthand through its projects. Alexander Filippov leads our European Commission-funded Increased Access to Electricity and Renewable Energy Production project in Zambia, where only around 14% of the population has internet access.

At the outset of the pandemic, “the government sent public sector employees to work from home,” says Filippov, “but most did not have internet at their homes, so they could not work.” To keep his program on schedule, Filippov dedicated a portion of the project budget to purchase internet data for government counterparts collaborating with his team.

In the near-term, development specialists like Filippov will continue to innovate in the face of connectivity challenges. But the trend toward further digitization of services and social interactions is clear. Ensuring that half the world is not left behind will require development practitioners to understand the causes of unequal access to the internet as well as potential solutions.

Even when the internet is technically available in a country, the price of connecting can be prohibitive. To get a sense for the scale of the problem, let’s look at an all-too-familiar activity for many of us: a Zoom call.

According to Zoom, a one-hour video call with average internet speed on a mobile plan in the US costs around $4, based on data collected by UK-based research firm Cable. And many users in high income countries access internet via broadband, making the call even cheaper. But in many countries, where mobile data is much more expensive than the US or Europe, it is also the go-to source for internet. For example, in Benin and Malawi that same Zoom call would cost $14 using mobile data—even more expensive given the comparatively lower incomes in much of the developing world. By combining the mobile data pricing and per capita income data from the World Bank, we can get a snapshot of the prohibitively expensive cost of the internet around the world.

The above chart displays the cost of a 1-hour zoom call as a percentage of the average monthly income per country. As we would expect, residents of poorer countries would need to shell out a much higher proportion of their income for the call, with those in the top left quadrant of the graphic paying an exorbitant amount (nearly a week’s salary in Malawi).

According to the UN, affordable internet is defined as no more than 2% of a person’s monthly income per Gigabyte of data (if we scale this down to the 540 Mb Zoom call mentioned above, this comes out to 1.08% of income). Malawi, Chad, Benin, Yemen, Congo, and others are well above this mark, and many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa fall just above or below the line.

Those countries with very high mobile internet costs tend to fall into a few categories: land-locked countries (Malawi, Chad, Central African Republic), fragile states (Yemen, Somalia), and small Island states (Kiribati, Solomon Islands).

DT Global’s Asia and Pacific Team (based in Australia) has witnessed the importance of expanding internet access to even remote islands. “Digital solutions are not silver bullets, but they are a very strong foundation for health, education, emergency responses, commerce, and economic development,” says Di Barr, Team Leader of the DFAT-funded PHAMA Plus Program that supports access to diverse export markets in the Pacific.

While internet connections remain spotty (and relatively expensive) in the region, digital communications still bring down the cost of travel between countries, and open doors to commerce and economic growth. When COVID-19 restricted travel to Pacific Island countries, food safety auditors from Australia could not access the region, threatening imports. DT Global’s team on the PHAMA Plus program helped develop a remote audit process to keep trade moving. The PHAMA team’s success illustrates a key challenge of digital acceleration. Digital solutions provide pathways for countries to surmount development challenges, but in turn these same countries become more dependent on digital infrastructure that is often aging and out of date.

While it may seem like only a matter of time before internet access is no longer an issue, the available data debunks this theory. In high income countries internet access has expanded rapidly, reaching 90 percent penetration in just the past 30 years. But in middle- and low-income countries growth has been much slower. Worse, of the 180 countries for which Cable collected data in 2018 and 2020, 19 experienced increases in the median cost of the mobile internet.

Some of these increases may be the result of price volatility (i.e., the price of data in these countries could very well swing in the other direction next year). But this illustrates a key point: we cannot simply wait for internet access to improve for the world’s poorest. This is, in part, because market conditions do not incentivize private companies to seek rural and disconnected customers.

A look at connectivity in Africa helps shed further light on this issue. For an African country to gain access to the World Wide Web, a private company (or in some cases the government) must construct a cable to connect to an undersea cable system that carries internet data from overseas. In the case of mobile internet, companies then connect mobile towers to these cables to provide internet to the surrounding area, typically with a range of around 10 kilometers. The map below displays the current extent of internet cables and population density in Africa.

While population-dense regions (such as North and Southern Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, and Ethiopia) are covered by many cables, more rural, but still populated, areas (represented by the green hexagons) have few cables. This is because it is more lucrative for multiple private companies to build a short cable and compete for the millions of customers within urban areas than to build a long cable to reach customers who are in rural areas.

The above market failure indicates a role for the public sector in solving the connectivity gap. Here are three specific ways development donors and practitioners can be a part of the solution:

Support public-private partnerships with data: After identifying areas where population density may not support the costs of a privately funded infrastructure project, governments and donors could offset the cost of a cable to incentivize private sector action. Historically, this type of effort has been hampered by the lack of available data on population density and internet use in rural areas. Today, recent improvements in data quality (such as the Global Human Settlement Layer dataset used to create the above fiberoptic cable map) can support these initiatives. Governments and the development community should continue to support the development, maintenance, and promotion of such datasets.

Improve the enabling environment: Regulations and, in some instances, state-backed monopolies limit competition among internet providers to drive up prices. As noted by Louise Williams, DT Global’s Senior Director for Desarrollo económico, “In the long run, although digital technology fosters exciting opportunities in innovation and connections among people, countries are not well served either by a tightly controlled or a ‘wild west’ approach to implementing digital ecosystems.” Williams emphasizes the benefits of establishing adaptable digital or broadband strategies that set a course for a country’s alignment with international best practice in legal and institutional infrastructure, managing both digital opportunity and risk. These best practices include a competitive telecommunications market, integrated principles of non-discrimination, open access to the internet (which includes speed and affordability), continuous public engagement and education on digital issues, and commitments to cybersecurity. Moreover, effective “digital governance” involves embracing the knowledge and research that the private sector brings to connectivity issues, while ensuring that the poor and disconnected are always part of a shared way forward.

Teach digital skills: Despite the market challenges explained above, researchers still believe that 75-80% of the world population will be online within the next two decades. But it is unlikely that this access will be equally distributed across the population. Divides in access by social status, gender, and income level are likely to persist. Development donors and practitioners can support these groups through digital skills building, access to resources, and encouragement (e.g., by championing women and minorities in the technology sector).

Our increasingly digitized world holds the possibility for both immense connecting potential and continued isolation for those populations most at risk. It’s critical that we find creative ways to lift the whole world with digital technology, not just it’s wealthiest inhabitants.