DT Global is excited to participate as a sponsor and speaker at the Australasian Aid Conference, February 17–19, 2020. The Australasian Aid conference brings together researchers from across Australia, the Pacific, Asia, and other countries to share insights on international development policy and practice. Our Australian and US DT Global colleagues are participating in the conference, and the post below highlights one of the panel topics that Sloan Mann, President of US Operations, and Orion Wilcox, Research Analyst, will be presenting on: evidence-based approaches to delivering better development outcomes using our analytical framework, Sensus.

Today’s conversation around international development is driven by two major trends. On the one hand, there is a consensus that foreign aid decisions need to be based on better evidence, which most often equates to hard data and rigorous evaluations. On the other hand, there is a long-overdue push toward more locally led development. Advocates of this approach argue that people living in developing countries should be seen not as beneficiaries, but as colleagues and drivers of their own development.

At DT Global, we are equally committed to both of these approaches. In fact, we believe that it is impossible for development to be evidence-based if it doesn’t put local communities in the driver’s seat. (After all, where exactly do we get our evidence?)

In order to square this circle, we developed an in-house approach, Sensus, to engage local partners in the design and ongoing testing of programs. Sensus helps local partners to identify the root causes of development challenges and then design sustainable solutions that mitigate the underlying causes of violence, instability, and community dysfunction. The methodology is rooted in the concept of action research, which seeks transformative change through the simultaneous process of taking action and conducting research.

Through Sensus, DT Global trains local partners—including NGOs, local government, activists and others—to collect data on the challenges facing their communities. Next, our team works with partners to analyze this data and design potential solutions using a Human-Centered Design approach. But this is only the first step. Every potential solution is only a theory to be tested. Over time, partners learn more about the problems in their community and why certain initiatives succeed where others fail.

Following the territorial defeat of the Islamic State (or ISIS), Iraqi communities faced a long road to recovery. In parts of northwestern Iraq where ISIS formed its so-called Caliphate, the war had destroyed most of the region’s housing stock and critical infrastructure and thousands of families had lost loved ones to the group’s violence. In the wake of this violence, the threat of long-term retributive violence extended to whole families and sometimes whole tribes. As the Iraqi government returned to northern Iraq, tens of thousands of people were forcibly displaced from their homes and herded into prison-like “rehabilitation camps” due to their perceived affiliation with ISIS. While some of these residents may have been supporters of the group, the vast majority were women, children, and elderly who were simply related to someone who had joined the group.

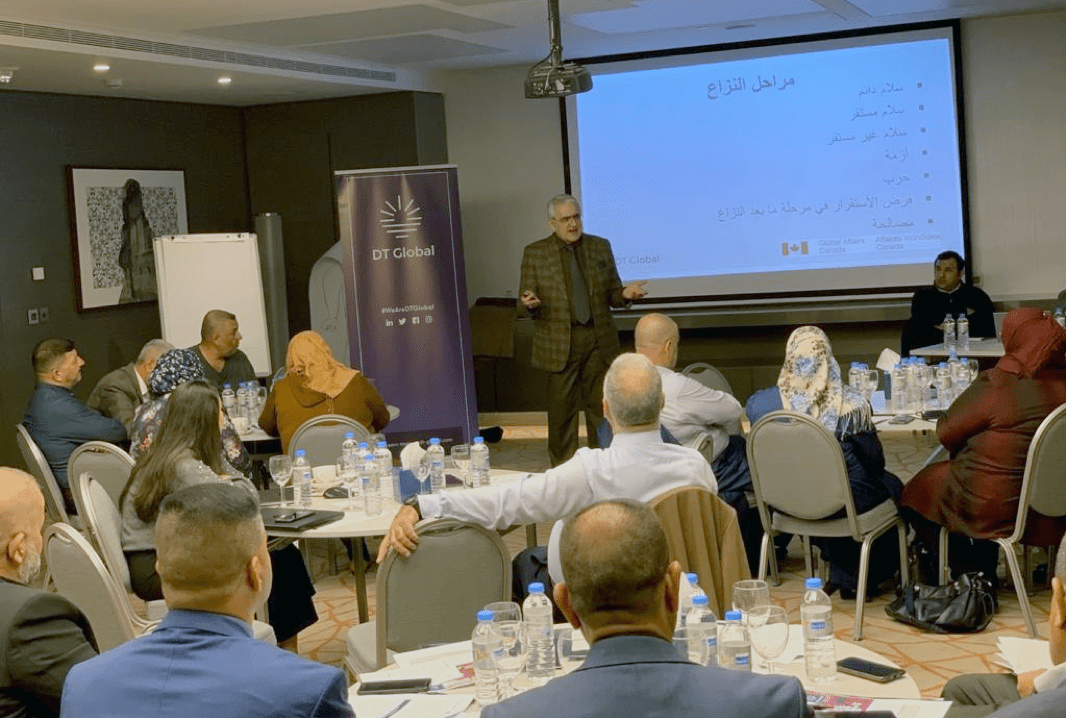

“We knew we needed to work with the local communities and the government to resolve disputes and re-integrate these families into society,” says Humam Rajab, who runs DT Global’s Preventing Reprisals and Mitigating Violence (PRMV) program, funded by Global Affairs Canada’s Peace and Stabilization Operations. “If we failed,” says Rajab, “the camps would be the breeding ground for ISIS 2.0.”

While significant academic literature on dispute resolution and restorative justice in post-conflict societies is available, Rajab knew that to be truly evidence-based, he needed to ground the program in the local context. Further, his team needed to provide communities with the skills to resolve these issues on their own.

“We needed to identify the root cause of the conflict, and give communities the tools to resolve these disputes,” says Rajab.

The first step was to better understand the nature of the conflict. The PRMV team trained local youth activists to conduct basic mixed-methods research, including surveys and focus groups, using simple-to-use mobile data collection technology. The youth identified a research question (“What is the driver of conflict in this area?”) and surveyed residents involved in each dispute. In parallel to this training, the PRMV team formed and trained inclusive committees of community leaders—local officials, tribal elders, youth and women activists, local police—on how to interpret the evidence collected and facilitate discussions around it.

After the data was collected and validated by the committees, the PRMV team conducted workshops with the committees to form a mechanism for resolving disputes. Often, the evidence showed that the key impediment to resolving disputes was tangential to the conflict itself. For example, in many cases, tribes who had lost their homes during the war were opposed to the re-integration of families from tribes perceived to be close to ISIS. But the reason behind this was that they were angry about not receiving compensation for their destroyed homes from the central government. With this knowledge, the program was able to use media to begin addressing tribes’ concerns on compensation and separate the re-integration issue.

“Our approach is based on positive deviance,” says Rajab. “We promote every success on social media to show other communities that we can resolve these issues in a methodical, impartial manner.”

To date, the PRMV program has successfully resolved dozens of ISIS-related disputes, preventing further bloodshed and allowing for the re-integration of hundreds of families into society. While there are still thousands in camps, Rajab believes that the program’s success is in creating a model that Iraqi communities can build on.“In these communities, officials are accustomed to making decisions on their own. They aren’t used to seeking others’ opinions and making decisions based on evidence,” says Rajab. “With this project, we changed that. And that will be the long-term impact of this program.”